Habit Change as a Design Problem

Friction, defaults, and identity can reshape your daily life.

Tom used to think his habits were a moral test. If he scrolled late at night, he felt “lazy.” If he ate sugar when stressed, he felt “weak.” But after tracking his days for a week, he saw a different picture: his choices were not random. They were predictable.

One evening, Tom opens a simple table on his laptop. In seven days, he finds three repeating loops:

- boredom + couch → social media → easy stimulation

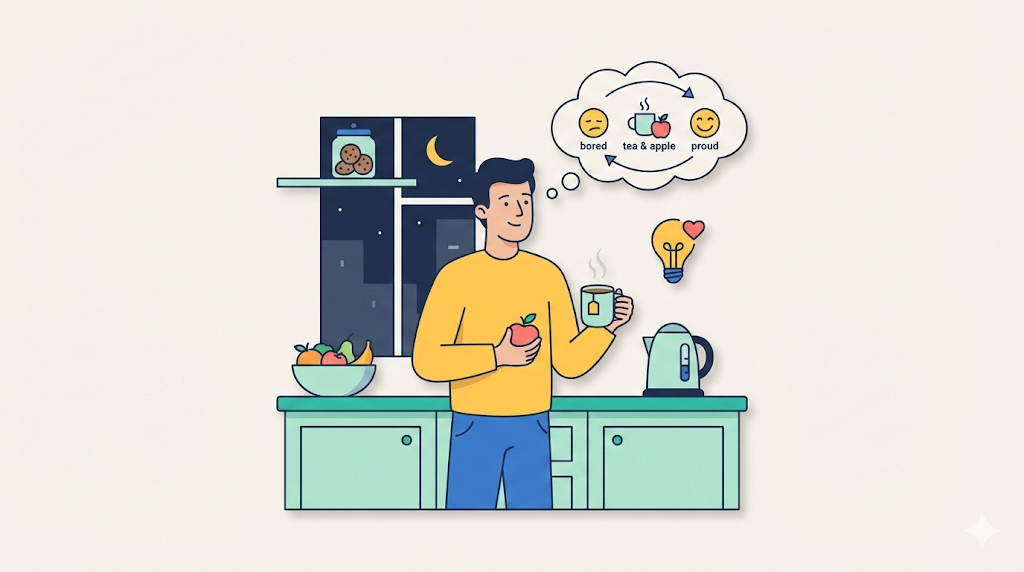

- stress + kitchen → cookies → quick relief

- fatigue + bed → scrolling → escape from thinking

He realizes something important: the cue is often outside him, and the reward is often designed to be fast. In a world of one-click delivery and endless feeds, fast reward is everywhere. Many work and media discussions (for example, in WEF-style reports about attention and well-being) warn that constant digital cues can drain focus and sleep. Tom does not need to read a report to feel it—his body already knows.

Reward prediction and the “next easiest action”

Modern products are built around immediate reward. A notification is a cue. One tap is a routine. A like, a new video, or a sweet taste is the reward. Your brain learns to predict that reward and pushes you to act before you even decide.

Researchers in behavior design, including the Stanford Behavior Design Lab (BJ Fogg), often focus on a practical truth: when motivation is low, the easiest action wins. So Tom stops asking, “Am I strong?” He asks, “What is my next easiest good action?”

He also works with timing. Late at night, his brain is tired, so he chooses a routine that is almost automatic: phone out, tea in, lights down, book open. He is not trying to be wise at midnight. He is trying to make midnight simple.

Friction, defaults, and choice architecture

Tom designs his environment like a small choice-architecture project.

- He adds friction to bad routines: removes apps from the home screen, logs out, turns off key notifications, and keeps cookies in an opaque box on a high shelf.

- He improves defaults for good routines: phone charger in the hall, walking shoes by the door, tea bags on the counter, and a book on the pillow.

- He creates a replacement kit: gum, herbal tea, a 5-minute walk playlist, and a short breathing timer.

These changes look small, but they change what happens in the first 10 seconds after a cue. Even at work, Tom makes a tiny redesign: he keeps his phone facedown, and he sets two short check times for messages. Fewer cues means fewer cravings.

Identity-based habits: who you become

Tom notices a deeper layer. If he frames the habit as “I am trying to stop,” he feels stuck. If he frames it as “I am a person who protects sleep,” he acts differently. The routine becomes a vote for an identity.

So Tom writes one sentence on a card:

“When the cue hits, I choose the sleep-protecting routine.”

He puts the card where he used to charge his phone. He also tells Lina his plan, because social support makes the new default feel more real.

Tom still slips sometimes. The goal is not perfection. The goal is fewer cues, more friction, and better defaults. Over time, the craving does not disappear, but it loses power—because the old path is no longer the automatic path. And that is what real self-control often looks like: not constant fighting, but smart design.

Key Points

- Your brain predicts rewards, so cues can push you before you “decide.”

- Friction and good defaults reshape what happens in the first seconds.

- Identity framing turns a routine into a long-term direction.

Words to Know

predict /prɪˈdɪkt/ (v) — guess what will happen next

immediate /ɪˈmiːdiət/ (adj) — happening right away

default /dɪˈfɔːlt/ (n) — the normal choice if you do nothing

architecture /ˈɑːrkɪtɛktʃər/ (n) — how parts are arranged and designed

identity /aɪˈdɛntəti/ (n) — who you believe you are

motivation /ˌmoʊtɪˈveɪʃən/ (n) — the drive to do something

drain /dreɪn/ (v) — slowly take away energy

automatic /ˌɔːtəˈmætɪk/ (adj) — happening without thinking

opaque /oʊˈpeɪk/ (adj) — not clear; you cannot see through it

stimulus /ˈstɪmjələs/ (n) — something that triggers a response

self-control /ˌsɛlf kənˈtroʊl/ (n) — managing your actions

well-being /ˌwɛl ˈbiːɪŋ/ (n) — health and life feeling